Home>>Cultures>>Chinese Beauty through the Changes of Time

Chinese Beauty through the Changes of Time

Women in China have traditionally been associated with the pursuit of beauty. For example, the Confucian scholar Liu Xiang ( c 77-6 BC) wrote "[she] takes delight in one's appearance" (1). The Chinese word 'beautiful' originally meant 'pleasant to sight' and is one of the earliest characters inscribed on oracle bones from 16-11 BC. However, standards of beauty have changed significantly throughout Chinese history. From slender to plump and frail to graceful, shifting ideals of feminine aestheticism in Imperial China can be traced through paintings, sculptures and contemporary accounts of women famous for their beauty. Although such women appeared as leading politicians and warriors, it was nevertheless from within a predominantly male-centred society that expectations of femininity were constructed. Conversely, the emancipation of women since the 1920s and increasing globalisation in the twenty-first century have effected further changes in ideals of beauty and fashion in modern China.

Western Han dynasty (206 BC - AD 8)

Founded by Liu Bang in 206 BC, this became one of the great dynasties of Chinese history. It was in this period that Confucianism was established as the main ideology of government in China.

Chao Fei-yen is reported to have been one of the most beautiful women in this dynasty. The Emperor Ch'en-ti was attracted by her slim and graceful figure. She displayed her agile body as a vivacious and energetic dancer. With her sister, Chao Hede, she used her beauty as a weapon against the Emperor, of whom she was a concubine. The government was thrown into chaos in an internecine struggle for power. Although she was ultimately unsuccessful, her story shows that strength and confidence were highly regarded as virtues in a woman during this period. This is in stark contrast to the frailty and wilting beauty that was later to be admired in the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties.

Chao Fei-yen is reported to have been one of the most beautiful women in this dynasty. The Emperor Ch'en-ti was attracted by her slim and graceful figure. She displayed her agile body as a vivacious and energetic dancer. With her sister, Chao Hede, she used her beauty as a weapon against the Emperor, of whom she was a concubine. The government was thrown into chaos in an internecine struggle for power. Although she was ultimately unsuccessful, her story shows that strength and confidence were highly regarded as virtues in a woman during this period. This is in stark contrast to the frailty and wilting beauty that was later to be admired in the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties.Similar strength of character and resilience can be seen in Wang Zhaojun, also highly regarded for her beauty during the Han dynasty. Having caught the attention of many at the refined and sophisticated Chinese court, Wang Zhaojun continued to flourish despite having been bargained in marriage to strengthen an alliance with the Huns in the wilderness of the Asiatic steppes.

Terracotta sculptures that survive from the Han dynasty reflect the tall, slender ideal of feminine beauty so admired by the Emperor. Tomb figures from this period strive to capture the life and vitality of the subject and are noted for their graceful, slender style. Robes worn by noble women during the Han dynasty had a long train that trailed behind, gracefully emphasizing the women's height and stature.

The Lienuzhuan

The Lienuzhuan , compiled by the Han Confucian scholar Liu Xiang, contains 125 biographies of exemplary women. Aiming to promote dignity and moral virtue as necessary components of beauty, the Lienuzhuan can be seen as an attempt to caution women against using their beauty to gain power as the sisters Chao Fei-yen and Chao Hede had done. Many stories maintain that external physical beauty is merely a manifestation of internal beauty in the form of virtue. The book contains several biographies of physically ugly women who nevertheless married emperors and became empresses as a result of their attractive, special inner qualities. Women lacking such virtue, on the other hand, are described as scheming to entrap men in sensual pleasures in order to distract them and fulfil their own selfish plans. These women are attributed with causing disruption and breakdown in families and the state. It appears therefore that, whilst not regarded as necessarily dangerous, beauty at this time was strongly linked to female virtue. As such, beauty could be displayed primarily through strength of character and moral disposition.

T'ang dynasty (AD 618 - 907)

The T'ang dynasty is renowned for the artistic and personal freedom it afforded women. Artwork from the period shows energetic, full-bodied women engaged in outdoor athletic sporting pursuits such as polo on horseback (2). Delicate features and plump faces in sculptures of aristocratic ladies of the T'ang dynasty convey the ideal image of feminine beauty. Ceramic figures of elegant female courtiers that were used as tomb furnishings in the period are known today as 'Fat Ladies' for their fleshy faces.

The T'ang dynasty is renowned for the artistic and personal freedom it afforded women. Artwork from the period shows energetic, full-bodied women engaged in outdoor athletic sporting pursuits such as polo on horseback (2). Delicate features and plump faces in sculptures of aristocratic ladies of the T'ang dynasty convey the ideal image of feminine beauty. Ceramic figures of elegant female courtiers that were used as tomb furnishings in the period are known today as 'Fat Ladies' for their fleshy faces.The origin of this standard of beauty can be attributed to the T'ang emperors' preference for plump women as a sign of wealth and privilege. An example of such a woman is Yang Kuei-fei, a heavy and robust concubine with whom the Emperor Ming Huang became infatuated. Known as the 'Jade Beauty', she is celebrated as one of the most beautiful women in Chinese history. Chroniclers at the time described her white skin and delicate features, comparing them to fine carvings in the jade with which she surrounded herself.

Song dynasty (AD 960 - 1279)

The Song dynasty was marked by a return to Confucianism and a desire to live a simpler life than in the former T'ang dynasty. Peace and economic security encouraged a flourishing of such educational and intellectual activity. This is reflected in a plainer style of dress for both men and women during this period.

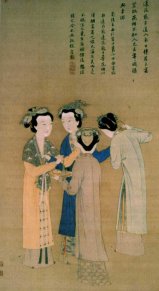

In contrast to the T'ang dynasty, women were now encouraged to remain indoors and to be seen by none but their husbands. It was socially expected that women should display their virtue physically. This expectation was instrumental in establishing the practice of footbinding during the Song dynasty. The physical limitations of bound feet were intended to emphasize female delicacy and vulnerability in comparison with superior male strength, thereby confirming men's sense of mastery over women. In effect, female subservience to men in Song society was encouraged as a display of the highest form of chastity and virtue. Attention to physical appearance was therefore crucial to women in attracting the interest of both powerful men for marriage, and husbands in competition with their other wives and concubines. Paintings commissioned by emperors during the Song dynasty portray women according to these presiding standards of graceful and plaintive beauty (3).

In contrast to the T'ang dynasty, women were now encouraged to remain indoors and to be seen by none but their husbands. It was socially expected that women should display their virtue physically. This expectation was instrumental in establishing the practice of footbinding during the Song dynasty. The physical limitations of bound feet were intended to emphasize female delicacy and vulnerability in comparison with superior male strength, thereby confirming men's sense of mastery over women. In effect, female subservience to men in Song society was encouraged as a display of the highest form of chastity and virtue. Attention to physical appearance was therefore crucial to women in attracting the interest of both powerful men for marriage, and husbands in competition with their other wives and concubines. Paintings commissioned by emperors during the Song dynasty portray women according to these presiding standards of graceful and plaintive beauty (3).Ming dynasty (AD 1368 - 1644)

Between 1279 and 1368, China was under the foreign domination of the Monguls. During this period, the Monguls restricted the assimilation of Chinese culture and attempted to preserve their own national character. Following the success of an uprising against the Mongols in the 1350s, a new Chinese dynasty with the name Ming was declared in 1368. The founder, Zhu Yuanzhang, aimed to restore a traditional Han cultural identity. The growth of urban prosperity and cosmopolitan entertainment can be contrasted with the solitude and reclusion expected of women. They were classed as outsiders as a result of male anxiety and warnings about the dangers of their beauty.

Footbinding became more widespread and severe during the Ming dynasty as the "symbol for feminine beauty, hierarchy and morality" (4). The author Wang Ping comments on poetry from the period, writing that "The women presented in these poems and literary works all have the same qualities: they are floating and weightless like unreachable treasure. Men cannot help feeling pity for them and falling in love with them" (5). The ideal of beauty portrayed in such poetry emphasizes sickness, fragility and suffering as much as it does delicacy, elegance and grace.

Footbinding became more widespread and severe during the Ming dynasty as the "symbol for feminine beauty, hierarchy and morality" (4). The author Wang Ping comments on poetry from the period, writing that "The women presented in these poems and literary works all have the same qualities: they are floating and weightless like unreachable treasure. Men cannot help feeling pity for them and falling in love with them" (5). The ideal of beauty portrayed in such poetry emphasizes sickness, fragility and suffering as much as it does delicacy, elegance and grace.However, the meaning of bound feet in the Ming dynasty was essentially grounded in eroticism. Bound feet were central to a woman's identity as an aspect of her beauty that she could control. An outpouring of novels, plays and poetry by female writers at this time highlights the erotic associations of bound feet. The 'Three Inch Golden Lotus' standard of perfection in foot length was therefore closely associated with an expression of sexuality. As such, footbinding formed part of a larger valorisation of passion, or qing, that is characteristic of the Ming dynasty. A high point of Chinese erotic culture, the cult of qing helped to bring explicit sensual and passionate significance to ideals of beauty in women.

Ch'ing dynasty (AD 1644 - 1911)

The conquest of the Ming dynasty by the Manchus in 1644 brought China under the authority of the Ch ing dynasty. The State attempted to regulate the sexual and gender roles of women through the prohibition of footbinding and the promotion of chastity in widowhood.

Although footbinding continued among upper-class women, as the historian Susan Mann writes, "the meaning of bound feet shifted away from eroticism and toward social responsibility" (6). In other words, footbinding became a mark of social elitism and feminine morality rather than a symbol of eroticism as it had been in the Ming dynasty. Indeed, 'beauty' was no longer a formal requirement in ideal standards relating to the role of women during this period. Women were expected to possess virtue and talent, but beauty as a suggestion of passion and sexuality was inhibited.

Although footbinding continued among upper-class women, as the historian Susan Mann writes, "the meaning of bound feet shifted away from eroticism and toward social responsibility" (6). In other words, footbinding became a mark of social elitism and feminine morality rather than a symbol of eroticism as it had been in the Ming dynasty. Indeed, 'beauty' was no longer a formal requirement in ideal standards relating to the role of women during this period. Women were expected to possess virtue and talent, but beauty as a suggestion of passion and sexuality was inhibited.The difference between ideals of beauty in the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties is revealed in the exclusion of all poems dealing with love, sex or romance from a collection of women's poetry by Wanyan Yun Zhu, published in 1831 (7). She wrote that, "in compiling this anthology, I have attached the greatest importance to purity of emotional expression and the harmony and elegance of rhymes poems about sexual love and romance by courtesans, whom earlier compilers anthologised profusely and rhapsodised over, are not included here."

Political, economic and social change (1911 - 1976)

Underlying currents of nationalist protest against Manchu authority in China fuelled the organization of a Republican movement in the 1890s. In 1911, Sun Yat-sen was elected provisional president of the Republic of China. Following the May 4 th Movement of 1919, nationalist movements involving large sections of the population aimed to push China towards modernization.

Increased contact with the West through trade and commerce brought many women in China together with new Western ideas of gender equality and women's rights. Not surprisingly, ideals of feminine beauty were influenced by women's emancipation and pursuit of education, employment and independence. The practice of footbinding declined and many women wore the cheungsam or qipao . In response to the shorter skirts seen in Western fashion, the cheungsam was tight fitting with high side-slits. It revealed more of a woman's body than any previous style of Chinese clothing. 'The Changing Face of Chinese Beauty' (8) details the rise in popularity of lipsticks, eyebrow plucking and shorter fringe lengths during this period, and the way in which women continued these practices surreptitiously during the Cultural Revolution (1966 - 76). These changing aspects of beauty symbolized the transition from more restrictive traditions to women s newfound freedom in China.

Increased contact with the West through trade and commerce brought many women in China together with new Western ideas of gender equality and women's rights. Not surprisingly, ideals of feminine beauty were influenced by women's emancipation and pursuit of education, employment and independence. The practice of footbinding declined and many women wore the cheungsam or qipao . In response to the shorter skirts seen in Western fashion, the cheungsam was tight fitting with high side-slits. It revealed more of a woman's body than any previous style of Chinese clothing. 'The Changing Face of Chinese Beauty' (8) details the rise in popularity of lipsticks, eyebrow plucking and shorter fringe lengths during this period, and the way in which women continued these practices surreptitiously during the Cultural Revolution (1966 - 76). These changing aspects of beauty symbolized the transition from more restrictive traditions to women s newfound freedom in China.Consumer culture and beauty industries (1976 - 2003)

The death of Mao Zedong on September 9 th 1976 heralded the end of an era and the beginning of an 'open-door' policy with further economic reforms in China. The first Chinese fashion magazine, Shizuang , or 'Fashion', was published in Peking in 1979. Receptive attitudes and experimentation with regard to Western fashion styles signalled a growing interest in personal appearance, beauty and consumer culture. Within this consumer culture, changing attitudes to women in China can be discerned. Female beauty became a commodity in a renewed importance of the expression of body and gender ideals. Consumerism provided an alternative arena for femininity outside the domination of the Party State.

However, a dichotomy between nature, tradition and China on the one hand, and culture, modernity and the West on the other hand, can be seen to underlie contemporary Chinese consumer culture. Whilst women in China are advised to make themselves 'modern', sexy and alluring, they are also expected to represent Chinese culture and values through the proper enactment of chastity and submission in their roles as housewives. The tension between these two ideals is expressed in magazine advertisements. For example, whilst advertisements for bust enhancers portray uninhibited women with natural curves symbolizing modernity and Western civilisation, those for skin care products tend to rely on pictures of chaste, shy women wearing traditional Chinese dresses in domestic settings. Similarly, the rising popularity of beauty pageants in China, with the Beauty Queen Guan Qi being crowned Miss China on September 21 st 2003, reveals a conflict between the desire to embrace a Western tolerance towards activities once suppressed as being bourgeois and decadent, and the need to justify the competitions in terms of providing suitable role models for women. An emphasis on the judgement of beauty in manners and education as well as in appearance is reminiscent of the traditional Chinese ideals of inner virtue and talent in women regarded as beautiful.

Furthermore, the export of American entertainment products such as films, music and MTV, together with the aim of opening markets for Western beauty products and technologies in China are reflected in the rapidly changing norms of attractiveness among Chinese women in recent years. As a result, the processes of globalization are implicated also in the establishment of beauty industries in China. Practices promoted by these industries typically include breast enlargements, skin whitening procedures, limb lengthening and the creation of 'double' eyelids. Cosmetic surgery is becoming increasingly popular as a means of altering the shape of noses and eyes to accord with Western appearances (9). Ideals of beauty in contemporary Chinese culture can therefore be seen to be attached to symbolic meanings based on China's transformation from a closed socialist society to a globalized consumer culture.

Sources

(1) In The Machinations of the Warring States , a 33 volume work by Liu Xiang ( c 77-6 BC) of the Former Han period.

(2) For example, the Tri-color Glaze Pottery Figure of a Lady playing Polo in the permanent collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

(3) For example, Looking in a Mirror by an Ornamental Box by an anonymous Song painter in the permanent collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

(4) Ping, W. (2000) Aching for beauty: Footbinding in China , Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

(5) Ping, W. Ibid.

(6) Mann, S. (1997) Precious Records: Women in China's Long Eighteenth Century , Stanford, Stanford University Press.

(7) Wanyan Yun Zhu (1831) Correct Beginnings: Women's Poetry of our August Dynasty (Guochao quixiu zhengshi ji).

(8) http://www.chinavista.com/experience/old/beauty.html

(9) BBC News, Chinese woman seeks perfect beauty , published 2003/07/24

Home>>Cultures>>Chinese Beauty through the Changes of Time